Did you know that NAEP (The National Assessment of Educational Progress) leads the way in publishing grade-level assessment content and National Standards (through the NAEP Frameworks) in the tested areas and grade levels? That’s right, since 1990, the Main NAEP study has led the way in setting national standards. NAEP trends and comparisons, its content and assessment frameworks, and released items and item maps are especially useful for checking on the levels of expectations in state and local education standards.

Introduction to Main NAEP in the 1990s

Although NAEP has conducted its Long-Term Trends (LTT) study since 1969, NAEP launched the “Main NAEP” study in 1990, introducing state-level comparisons in 1992 in four content areas: Mathematics, Reading, Science, and Writing, with writing results coming out less regularly than the other three.

In addition to providing statewide comparisons in these four subject areas, Main NAEP surveys more content domains than the NAEP LTT study, which only measures student outcomes in Reading and Mathematics. With Main NAEP, there are released content and assessment frameworks and released assessment items in 10 content domains including: Science, Writing, U.S. History, Civics, and Geography. These materials can be used in content alignment and benchmarking studies at the state and local education levels, alongside State and other National standards. NAEP content and assessment frameworks help inform state-level educational standards and can also support content alignment efforts in local districts and schools.

NAEP Achievement Levels

NAEP provides the U.S. with national benchmarks for student achievement in the tested grades (currently grades 4, 8, and 12).

Using its achievement levels—Basic, Proficient, and Advanced—NAEP describes what students should know and be able to do at each level in each subject. These descriptions act as a reference point for expectations, not as enforceable grade-level standards, but as a common yardstick across states, districts, and demographic groups.

NAEP illustrates these performance levels both by providing general descriptions of student proficiency, and by linking released items to these performance levels in their famous Item Maps (we will explore the NAEP item maps later in this series). For example, in Grade 4 Reading, NAEP descriptions of student performance at each level include students’ ability to demonstrate:

- Advanced – consistent higher-order thinking in reading, identifying literary devices and producing well-supported and thoughtful responses to comprehension questions;

- Proficient – solid academic performance as they demonstrate both literal and inferential comprehension of text;

- Basic – some reading skills including understanding of the overall meaning of text, demonstrating literal comprehension; and

- Below Basic – limited reading skills as (the students) often have difficulty decoding and struggle with literal comprehension.

Useful Ways of Using NAEP’s State-by-State Proficiency Rates

A major component of Main NAEP in Reading, Mathematics and Science is the publication of average state-by-state proficiency rates, both across all students and for particular student demographic groups such as students who live in low-income households, and students who are English language learners. These state averages are calculated from carefully selected samples that are representative of each state’s unique population characteristics. Because the state-level demographics are different for each state, this means that some of the proficiency rate differences across states reflect differences in state demographics. But that doesn’t mean that these state averages aren’t helpful, nonetheless.

Given this caveat about reading too much into the state-by-state differences in average proficiency rates across states, there are two very useful ways of using these comparisons: a) looking within a particular state at the patterns of the state’s average proficiency rates, and b) again looking within and across states, at the NAEP proficiency rate trends, compared to the proficiency rate trends on the state test. In this blog, we look comparisons between NAEP proficiency rate averages and State proficiency rate averages.

Within-State Proficiency Rate Trend Comparison

Let’s start out by saying that the NAEP Achievement levels do not denote grade-level performance, and instead “demonstrate solid academic performance and competency over challenging subject matter.” NAEP’s challenging proficiency level has been shown to correspond to taking high-level high school courses, and is a good predictor of higher standards denoted in succeeding in the first year of college (Davidson, A., 2025). NAEP has also been shown to the U.S. performance on the international assessment, TIMSS (NCES, 2014). Thus, used as external benchmarks, NAEP achievement levels can help us to evaluate the extent to which our students are meeting higher levels of expectations needed to succeed in college and to keep pace with students performing well in other countries.

Examining external benchmarks for key academic indicators help us to gauge the levels of expectations in our Nation, State, Districts, and Schools. This can be done by examining the results and artifacts published in an external testing program like NAEP and then comparing these results to our States or Districts.

Data in this Tableau Public Workbook, “state naep” compares the percentage of students achieving the Proficient level on NAEP to the percentage achieving the proficient level (or its corollary) on the state test in Reading and Mathematics at grades 4 and 8. Ideally, the proficiency rates across the two tests would be comparable as this would indicate that the state tests set a proficiency standard that is similar to that on the national assessment. States with much higher proficiency rates would appear to have set much lower learning standards than NAEP Proficient.

Graph #1: State-NAEP “Standards Gap” Grade 4 Mathematics

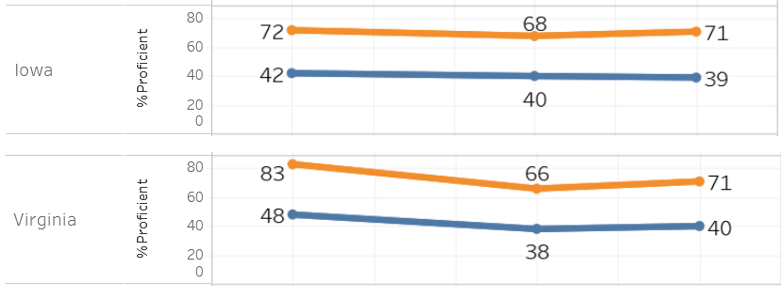

This Tableau Public worksheet visualizes the proficiency trends on State Assessments vs. NAEP for the years: 2019, 2022, and 2024. These data are taken from the excellent article published by Toch and DiMarco (2025), in their FutureEd article, “The New NAEP Scores Highlight a Standards Gap in Many States.”

Tableau Public Views of “state naep”

There are two sets of worksheets per content domain and grade. The first worksheet in each pair shows the “standards gap” between proficiency on the state test vs. proficiency on NAEP in the latest testing year, 2024. Larger values indicate that the proficiency rate on the state test is higher than the proficiency rate on NAEP. For example, both Iowa and Virginia appear to have much higher proficiency rates on their respective state tests, in both Reading and Mathematics, at grades 4 and 8, than on NAEP, suggesting lower standards. The Iowa website indicates that their state standards are based on the rigorous Common Core State Standards in both ELA and Mathematics. However, the state may have set a low cut score to signify proficient. Additional information is needed to better understand the disparity. Similarly, the Virginia DOE publishes a number of standards-related documentation for their “Standards of Learning” including Performance Level Descriptors that suggest rigorous standards; however, they may not fully align with the Common Core State Standards, or the test items, themselves, may not fully capture this level of rigor, or again, the cut score denoting proficiency on the test may be set at a low level. Again, additional investigation is needed.

One AIR (American Institutes of Research) study surveyed states on their use of NAEP in setting standards. The findings show that NAEP is used “not at all” or “only a little” by most states when setting state-level standards. Graph 1 is evidence of this lack of attention to national standards by some states (Behuniak & Way, 2022).

The second set of graphs for Grade 4 Mathematics show trends in proficiency rates on the state test vs. NAEP for the years 2019, 2022, and 2024. Here, we see that the disparities in proficiency rates between the state tests and NAEP persisted for both states. We encourage readers to review these comparisons between state proficiency and NAEP in the “state naep” Tableau Public workbook. Interested readers may wish to include their observations in the comments section.

Graphs #2 and #3: State Trends on the State test vs. NAEP in 2019, 2022, and 2024 in Iowa and Virginia, Grade 4 Mathematics

The Importance of Benchmarking Studies

Without external benchmarking data, educators at all levels are missing key information to evaluate local expectations. The Main NAEP study provides one set of benchmarks for conducting this important work.

These proficiency rates reports are just one piece of benchmarking information provided by NAEP. States and local agencies can also use benchmarking information provided in the NAEP Frameworks and in the NAEP released items and Item Maps. Subsequent blog posts in this series will provide insights for using these other pieces of information to evaluate the appropriateness of expectations used at the state, district, school, and classroom levels.

References:

Behuniak, P., & Way, D. (2022, March 14). White paper to provide context for NAEP achievement levels by reviewing state and international practices [White paper].

American Institutes for Research. Commissioned by the NAEP Validity Studies Panel.

Davidson, A. H. (2025). NAEP Achievement Levels Validity Argument Report. National Assessment Governing Board; Manhattan Strategy Group. ERIC (ED 672655).

National Center for Education Statistics. (2014, October). 2011 NAEP-TIMSS Linking Study: Technical report on the linking methodologies and their evaluations (NCES 2014-461). U.S. Department of Education.

Toch, T., & DiMarco, B. (2025, February 20). The new NAEP scores highlight a standards gap in many states [Explainer]. FutureEd.

Leave a Reply