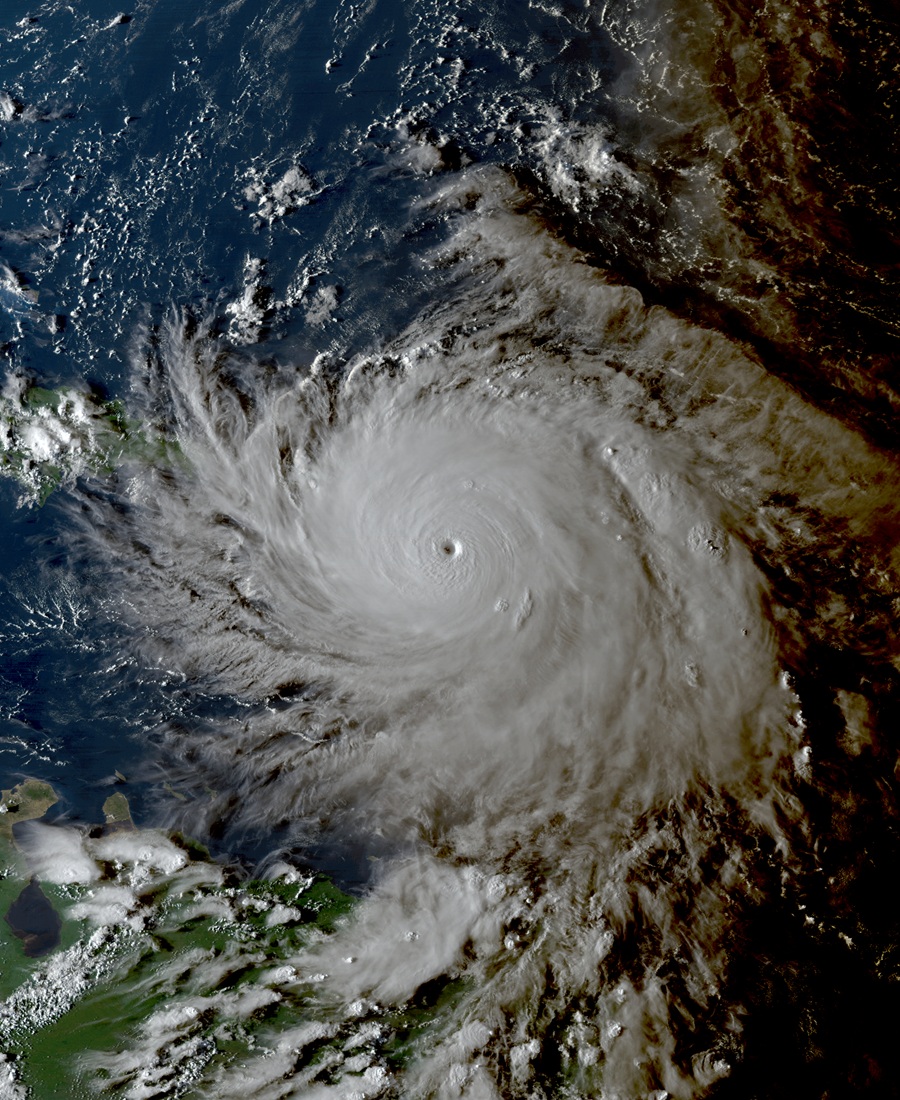

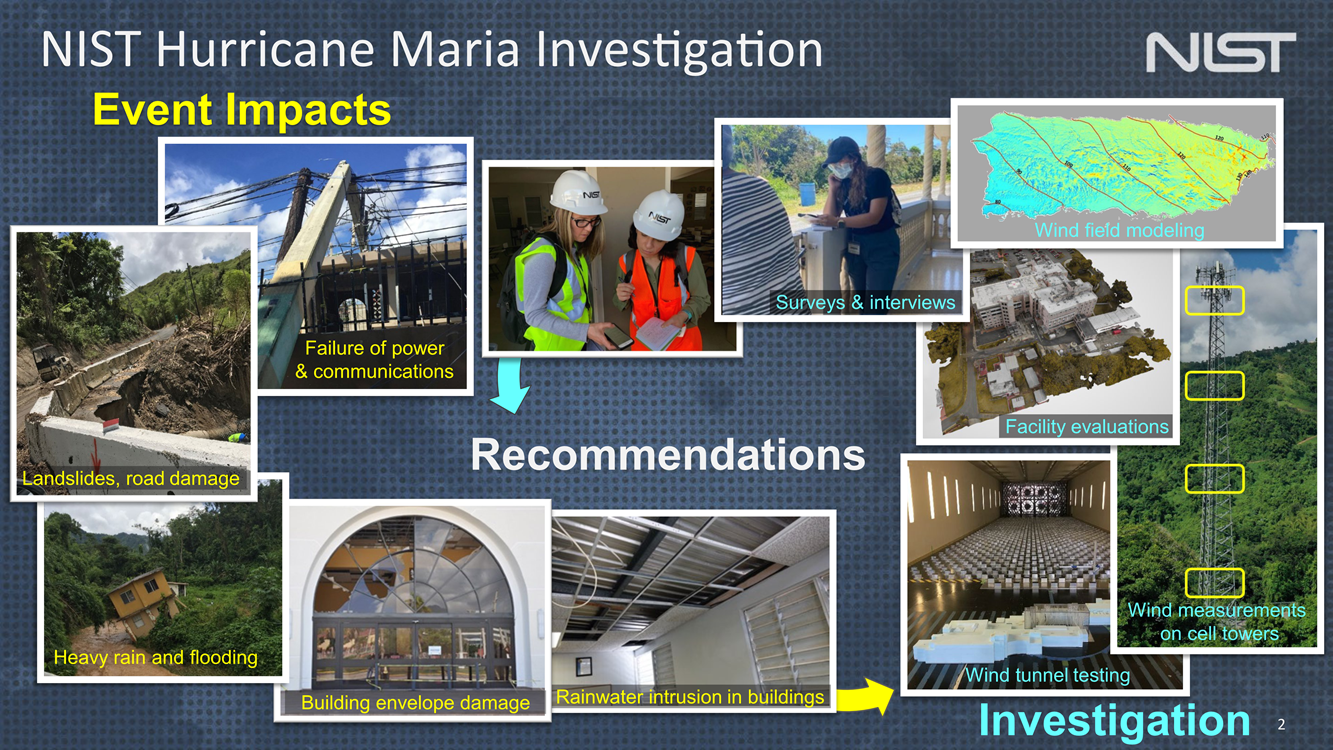

Though Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico eight years ago this month, in September, 2017, it was the strongest storm to hit the island in almost 90 years, causing $90 billion in damages and nearly 3 thousand deaths. U.S. government researchers are still working to build a full picture of the disaster and its lessons. In 2018, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) began a years-long study into Maria’s impact so their findings can inform future efforts to prepare for emergencies and build resilient infrastructure.

Results of that investigation are scheduled for release next year, but NIST released preliminary findings in July. Among these tentative results, NIST reported that 95.3% of Puerto Rico’s schools lost power for, on average, over a hundred days. Besides the loss of electricity, many schools also lacked potable water, with one school reporting that students needed to bring their own water from home.

Education is a long-term investment. While wildfires, heatwaves, and floods can disrupt students’ educations at all grade levels, the impact of natural disasters on education cannot be fully understood without longitudinal measures. (See, e.g., Crnosija, 2024.) When Hurricane Katrina made landfall in and around New Orleans in August 2005 (killing over 1.3 thousand people and causing $125 billion in damage) this disaster coincided with the timeframe of the 2004-2009 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:04/09).

BPS is (or was) a nationally-representative longitudinal sample study of first-time beginning postsecondary students in the 50 United States as well as D.C. and Puerto Rico. BPS was conducted by the National Center of Education Statistics about every eight years since 1990. BPS:04/09 followed the postsecondary progress of students who began college in 2004.

When Katrina struck in 2005, the devastation forced the displacement of 370,000 children and adolescents (200,000 in Louisiana alone), with one principal reporting that their staff “had to deal with personal problems that included home repair, car repair, and clearing of land on their private property. They had to work plus shuffle their time in getting their personal self and family back to a normal life.”

At this time, BPS staff were early in the planning process for a 2006 midpoint data collection, which would capture three-year outcomes for BPS sample members. Reasoning that postsecondary researchers might be interested in whether a major natural disaster like Katrina impacted the postsecondary progress of college students, BPS staff added several hurricane-related items to the 2006 BPS survey, asking respondents if and how 2005’s hurricanes affected their enrollment plans.

It is difficult enough to study the effects of one natural disaster. But due to the destabilizing effects of climate change, events like wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes are occurring at growing rates. As these events become more common, it will be increasingly difficult for education researchers to ask sample members about the full range of extreme weather events that may affect their education progress.

While developing the most recent BPS data collections, BPS staff struck upon the solution of incorporating disaster declaration data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). These data include longitudinal, geographical records of events including floods, cold and heat waves, earthquakes, hurricanes, storms, landslides, tornadoes, and wildfires. By incorporating these data into BPS releases (matching them to students’ institutions based on their locations), BPS could permit analysts to look at the long-term impacts of a fuller range of natural disasters.

Best of all, by using public administrative data instead of survey questions, BPS staff would better balance ambition, utility, pragmatics, and (most importantly) the rights and experiences of the sample members by keeping burden on survey respondents to a minimum. Besides, data quality is improved when we reduce reliance on self-report in favor of more rigorous measures.

Unfortunately, the mass cancellation of NCES research contracts including BPS and many other studies means that we were unable to release the BPS:20/22 files that would have included these FEMA data at a time when weather research is becoming increasingly more important.

The 2024 hurricane season, which included multiple category 5 hurricanes, was unusually active and destructive, causing 437 fatalities and $130.4 billion in damages. We are now well through the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, which began in June and will end by December. Both the 2024 and 2025 hurricane seasons overlap with the planned time frame for the BPS:20/25 study, which would have extended the BPS study timeline to include the 2024-25 academic year.

But this collection was prevented by the same contract cancellation that still delays release of the BPS:20/22 files.The base year of this collection overlapped with the 2020 hurricane season, which was itself the most active hurricane season on record at the time. (This season coincided further with a January magnitude 6.4 earthquake that delayed the start of spring semester for many Puerto Rico public school students.) Without these data, it may be harder for researchers to determine what, if any, immediate or long-term impact many of these natural events will have on the persistence and attainment of U.S. postsecondary students. Like anybody who has studied in Puerto Rico, I can tell you that the weather keeps coming even when the data stops.

David Richards was formerly employed by the National Center for Education Statistics, where he was study director for the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study.

Leave a Reply