“There is going to be no higher return on investment than what you’re going to see in that investment in a child from zero to three.”

– Maryland Governor Wes Moore

Maryland Governor Wes Moore isn’t just a politician. He’s a former finance professional who understands return on investment. At the Zero to Three Learn Conference this past October, he argued that the smartest investment is in early childhood education and care. The payoff from early childhood programs dwarfs the cost of rehabilitation later. This makes sense since our brains are most malleable in the first five years of life when brain development is quicker than in any other period1. During this time, the essential brain connections that are made lay the foundation for higher-level abilities like problem-solving, empathy, and self-control2. Early childhood is the time to ensure that children are on the road to success.

Currently, states and cities are realizing the value of investing in our youngest learners. In fact, public pre-K programs recently saw the biggest boost in state funding ever and according to the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), enrollment in these programs increased 7% between the 2022-23 and the 2023-24 school years3. This past November, a group of New England mayors4 convened in Providence, RI to share ideas on improving access to and quality of PreK programs. At least four states and the District of Columbia offer universal PreK to four-year-olds. Additionally, eight more states offer universal eligibility, permitting all four-year-olds to apply for enrollment, although available spaces may not accommodate every applicant. Moreover, some cities, like Boston, have their own programs.

In addition to expanded investments in PreK programs, a growing movement is pushing for universal access to free child care. Last month (November 2025), New Mexico became the first state to guarantee free child care for all residents, aiming to strengthen its economy while addressing challenges in education and child welfare. Connecticut recently passed a bill providing free child care for those earning less than $100,000 a year and capped the child care costs for those earning above the threshold at no more than 7% of their income. Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York, emphasized the implementation of universal child care at no cost as a key component of his campaign platform. Together, these efforts reflect a broader recognition: child care is not only an educational investment but also an economic strategy and a commitment to family well-being.

Investing in Early Childhood Works, But Only If Done Right

Research has demonstrated that scaling up quality preschool programs is harder than it looks on paper. A fine example of this fact can be found in the experience of the Tennessee Voluntary PreK (VPK) program. In 2005, the Tennessee state legislature passed a bipartisan package to establish high quality PreK classrooms for the state’s growing number of at-risk four-year-olds using excess lottery funds5. The program seemed to be a success, so the Tennessee governor pushed to expand the program. After scaling up, Vanderbilt University was hired to evaluate the short-term and long-term effects of the program. Surprisingly, they found that the effects of the VPK program disappeared by the end of the kindergarten year6. In fact, by third grade, the study showed that kids who had gone to VPK had poorer academic and behavioral outcomes compared to their classmates, raising doubts about the value of large-scale investments in early education.

Yet a closer look suggests that Tennessee encountered challenges scaling up the VPK program that compromised quality. For example, enrollment in VPK increased so quickly that it was difficult to monitor and maintain the program’s quality6. Research overall suggests that investing in early childhood programs is a worthy endeavor, but the Tennessee VPK experience underscores the need for careful and intentional implementation to protect the quality of the experiences for children and families7 during a scale up, taking steps to ensure that the programs best serve children, families, and society.

The Early Years Are Not K–12

Expanding K-12 programs is not the same as scaling up quality early care and education programs, as the VPK experience demonstrated. Young children need more support and attention than school-aged children and this makes expansion both challenging and expensive. To provide quality universal PreK or child care, investments need to be made in several areas, including facilities and staffing (capacity), professional development, and research and evaluation to ensure that the needs of children and families are being met.

Capacity: Facilities and Staffing

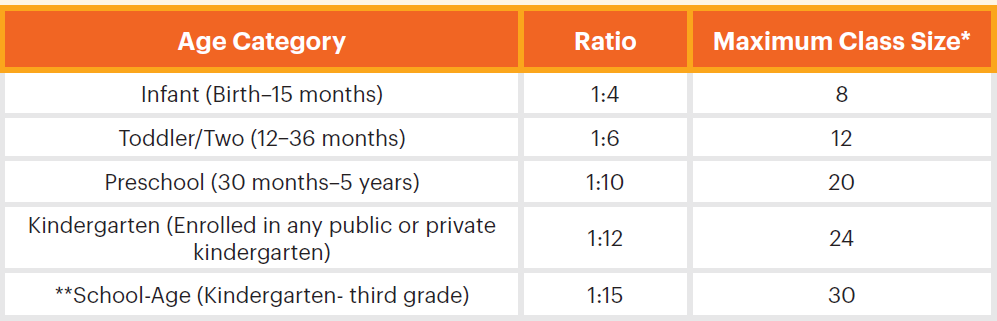

State and local governments typically underestimate the financial investment needed to procure the space and staff to expand high quality early education and care programs. This is because child care and PreK classrooms require more staff and fewer children than found in elementary school classrooms. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) recommends a ratio of one teacher to: four infants, six toddlers and ten preschoolers or PreK students (see table below). Consequently, offering universal child care or PreK requires more classrooms and more staff than is needed to expand kindergarten programs. Though New Mexico now offers universal free child care to all its residents, they currently do not have enough spots for all of New Mexico’s children, especially in smaller rural towns8. In response, New Mexico has announced that it is investing an additional $12.7million and is also reaching out to businesses and schools to increase the number of locations that offer child care. They are also actively recruiting new people to provide in-home childcare to create more slots.

Capacity is a big challenge for New York City as well10. Due to the small teacher child ratios needed for infants and toddlers, New York City plans to lean on home-based care providers to create more slots. However, the number of home-based care providers has dramatically reduced in recent years. The home-based childcare chapter of the United Federation of Teachers says that in 2007 there were about 28,000 home-based providers. Today there are just 12,000. This decline is attributed to a multitude of factors. Programs have lost students and staff to universal PreK programs, which pay better. Many home-based providers have left the field because of poor pay. Many home-based programs had to close during the COVID pandemic and did not reopen. Lastly, the current immigration policies have further strained this immigrant heavy workforce.

Recruiting staff is only the beginning. Without retention, the whole system unravels. Building real capacity means investing in the people who make it work. As PreK and child care programs expand, retention becomes non‑negotiable. Big investment is needed in salaries to retain staff. For example, in New York City providers’ median income is $25,000 whereas the median yearly salary of public school teachers is close to $100,00010. Research shows that poor salaries drive current staff out of the field and prevents new staff from joining the workforce. What is left is high turnover which undermines the quality of these programs and contributes to the staffing crisis11. New Mexico recognizes the value of retaining staff, explaining that staff who stay foster lasting relationships with the children and the families they serve. To raise salaries, New Mexico officials plan to offer incentivized rates to centers that raise salaries and extend hours, giving them funds to better cover their real costs8. New York City is also budgeting to bring child care providers salaries more in line with their K-12 counterparts.

Professional Development

Yet providing the space and the people does not ensure the quality of the programing, as we saw in Tennessee. To ensure that children benefit from these programs and enter school ready to learn, investments must be made in teacher and provider training. Staff need to be trained to facilitate learning and growth. Yet, the U.S. does not yet have a career path for those who provide early education and care to our youngest students. Unlike the K-12 system, there lacks a general expectation around training for providers and teachers of young children. To ensure that our investment in large scale early education and care programs pays off, we need to provide programs with both structural and process quality. Structural quality refers to the physical environment. As mentioned, there needs to be a small teacher to child ratio. Classrooms need to be equipped with toys children can manipulate and explore. Children need equipment to play on that promotes motor skills and coordination. Process quality refers to how the teacher interacts with the children. The teacher needs to be warm and responsive and help the child feel safe to explore and play. When staff turnover is low, children and families experience consistency with their child’s teacher and trust is fostered, bolstering process quality. Continuity of care bolsters process quality because it permits teachers to get to know individual children and learn how best to interact with them to promote learning.

Children learn best through play and exploration12. Teachers and providers need to understand how to capitalize on children’s play activities to promote both cognitive and social emotional learning. When teachers understand how to structure games, build on students’ ideas, and guide child‑led play toward clear learning goals, meaningful growth follows. For example, a teacher might add math activities to a board game to allow for the practice of numerical thinking and spatial skills13. Teachers need training and professional development to be able to easily incorporate learning goals into children’s everyday activities. In the absence of this training, the quality of the child care or PreK program is diminished.

Research and Evaluation – Is it working?

Lastly, as the Tennessee VPK experience illustrates, any expansion of early childhood programs must be accompanied by rigorous evaluation to safeguard both structural and process quality. At each stage, the program’s capacity to meet the needs of children and families should be systematically assessed to ensure sound implementation. Without such oversight, investments risk falling short of their intended outcomes and may ultimately prove ineffective. Continuous evaluation is therefore not optional; it is essential for the successful growth of childcare and Pre-K initiatives. The specific components of this evaluation will be explored further in Part 2 of this blog. As Rachel Maddow says, “Watch this space.”

Final Reflections

“This is not just a children’s issue, it’s an economic issue. Child care is what makes Maryland work. When families can afford care, our future workforce is better prepared and our current workforce prospers.”

Maryland Governor Wes Moore

The pandemic shuttered many early childhood programs, but it also underscored their vital role, not only in giving children a strong start but in fueling local economies. As Maryland Governor Wes Moore stated 14in his 2025 budget proposal, “This is not just a children’s issue, it’s an economic issue. Child care is what makes Maryland work. When families can afford care, our future workforce is better prepared and our current workforce prospers.” When parents and guardians have access to affordable, high‑quality child care and PreK, they can enter the workforce with confidence. And when their children thrive in those programs, parents are able to fully contribute to workplace success.

Quality does not happen by chance. It requires sustained investment in acquiring the space and staff needed (capacity), staff training and professional development, and ongoing systematic evaluation. With these supports in place, child care and PreK programs become engines of opportunity, nurturing the next generation of leaders and achievers.

The payoff from investing in early childhood is transformative. When children experience high‑quality learning during their most formative years, the result is thriving adults and a stronger economy for everyone.

- Wisconsin Council on Children and Families. (2007). Brain development and early learning. In Quality Matters: A Policy Brief Series on Early Care and Education: Vol. Volume 1 (pp. 1–2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED526797.pdf ↩︎

- First Things First. (2025, July 30). Brain development – first things first. https://www.firstthingsfirst.org/early-childhood-matters/brain-development/ ↩︎

- Heubeck, E. (2025, September 29). As Pre-K expands, here’s what districts need to know. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/as-pre-k-expands-heres-what-districts-need-to-know/2025/09 ↩︎

- Vilcarino, J. (2025, November 24). How one mayor is working to expand Pre-K access. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/how-one-mayor-is-working-to-expand-pre-k-access/2025/11 ↩︎

- Voluntary Pre-K fact sheet. (n.d.). Tennessee Department of Education. Retrieved December 11, 2025, from https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/early-learning/Voluntary_Pre-K_Fact_Sheet.pdf ↩︎

- Snow, K. (2015, October 1). Making sense of the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K study. www.naeyc.org/resources/blog. Retrieved December 11, 2025, from https://www.naeyc.org/resources/blog/tennessee-voluntary-pre-k-study ↩︎

- Gibbs, C., Weiland, C., Bassok, D., Phillips, D. A., Stipek, D., & Cascio, E. U. (2022, February 10). What does the Tennessee pre-K study really tell us about public preschool programs? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-does-the-tennessee-pre-k-study-really-tell-us-about-public-preschool-programs/ ↩︎

- Dadani, S. (2025, October 25). Capacity issues may limit New Mexico’s universal child care program. New Mexico in Depth. https://nmindepth.com/2025/capacity-issues-may-limit-new-mexicos-universal-child-care-program/?utm_source=Chalkbeat&utm_campaign=091d3c7c%E2%80%A6 ↩︎

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2018b). Staff-to-Child ratio and class size. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/accreditation/early-learning/staff_child_ratio_0.pdf ↩︎

- Elsen-Rooney, M. (2025, November 12). Mamdani’s $6 billion universal child care plan: How will NYC fund, staff, and scale up the program? Chalkbeat. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newyork/2025/11/11/mamdani-universal-child-care-pledge-faces-operational-challenges/?utm_source=Chalkbeat&utm_ca%E2%80%A6 ↩︎

- Commission on Early Childhood Educator Compensation. (2024). Compensation means more than wages: increasing early childhood educators’ access to benefits. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/user-73607/naeyc_benefits_brief.may_2024.pdf ↩︎

- Principles of child development and learning and implications that. (n.d.). NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/principles ↩︎

- Incorporating developmentally appropriate practice in Pre-Kindergarten expansions. (2024, April 9). American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/resource/field/incorporating-developmentally-appropriate-practice-pre-kindergarten-expansions ↩︎

- Governor Moore visits Montgomery County Early Learning Center for Roundtable on Child Care Accessibility and Affordability – Press releases – News – Office of Governor Wes Moore. (n.d.). https://governor.maryland.gov/news/press/pages/governor-moore-visits-montgomery-county-early-learning-center-for-roundtable-on-child-care-accessibility-and-affordability.aspx ↩︎

Leave a Reply